By Ebonee Johnikin, Communications Director, Foundation for the Mid South

In Coahoma County, a teacher might be rewarded with something as simple as a free drink at a local restaurant. It’s part of the Big Apple Campaign—a grassroots effort to remind educators that their work matters in a region where vacancies number in the hundreds and support often feels scarce.

Small gestures like these were among the stories shared during the Foundation for the Mid South’s recent webinar, Raising the Bar for Mississippi’s Students.

For 35 minutes, a panel of educators and community leaders confronted Mississippi’s biggest education challenges head-on: a growing teacher shortage, student mental health, and how families can move from the margins of school life into the center of decision-making.

A Teacher Shortage With Real Consequences

Mississippi is currently grappling with nearly 3,000 teacher vacancies. In the Delta, the number of newly issued licenses has dropped by 50% since 2018, leaving many classrooms staffed by alternately certified teachers with minimal training.

“Certification alone isn’t enough,” said Dr. Adrienne Hudson, Executive Director of RISE, Inc. “Teachers mold the minds of young people and, by doing so, determine not only how well students will perform later in life, but how strong or weak a community will become.”

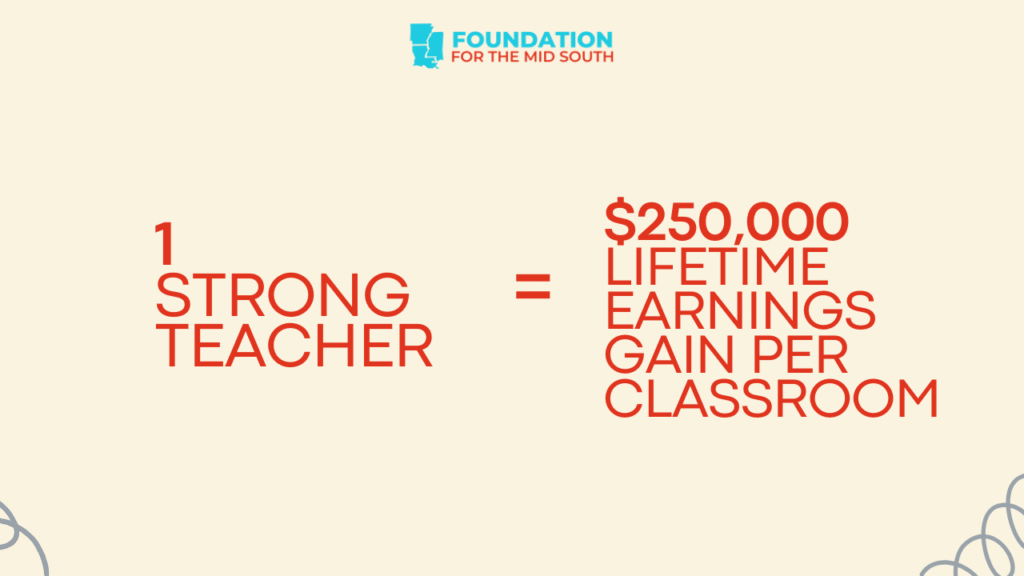

She noted that research shows teacher quality is the single greatest in-school factor affecting student outcomes. “One strong teacher can advance student learning by a grade level in a single year,” she said. “An ineffective teacher has the opposite effect.”

Hudson pointed to research by economist Raj Chetty showing that one strong teacher can increase a classroom’s lifetime earnings by $250,000 and raise the likelihood of students attending college. “That’s the kind of impact we’re talking about,” she stressed.

The solution, she argued, isn’t only about recruiting teachers but retaining them. “We’ve been facing shortages for over 20 years,” Hudson said. “It’s going to take recruitment, retention, and cultivation. And it’s going to take intentionality.”

Teaching the Whole Child

For Dr. Clayton Barksdale, Executive Director of the West Mississippi Education Consortium, the problem isn’t only about filling positions. It’s about what happens inside the classroom once teachers are there.

“Frederick Douglass said, ‘It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men,’” Barksdale reminded the audience. “Right now, we’re seeing a lot of broken children being overlooked because of the pressure of testing.”

He argued that Mississippi’s accountability system is too narrow.

“Right now, schools are judged only on math, English, and science scores. That’s short-sighted. If schools were also measured on parental involvement, behavior, and SEL programs, priorities would shift overnight.”

Barksdale has seen the power of embedding social-emotional learning (SEL) into daily instruction. As a principal, he set aside Wednesday mornings for 15-minute lessons on character traits like anger management and conflict resolution. “It wasn’t extra,” he said. “It was part of building strong children.”

He added that SEL isn’t just about students. Teachers need it, too. “One of my staff members lost her grandmother on January 10,” Barksdale recalled. “Every year, around that time, she struggled. So, I made it a point to give her a note of encouragement. Recognizing the tough days, not just the good ones, mattered deeply.”

Families at the Table

Dr. Shequite Johnson, an Assistant Professor at Mississippi Valley State University and a mother of five, has lived the challenges of engaging families in schools.

“Parents don’t want to only hear bad news,” she said. “A positive phone call from a teacher can completely shift the relationship.”

She urged schools to meet families where they are. “We need advisory boards, curriculum nights in community centers, and workshops that serve both students and parents,” she explained. “When families are included from the beginning, they stop seeing themselves as outsiders and start showing up as co-advocates in their children’s education.”

Johnson also reminded listeners that circumstances matter. “In the Delta, transportation is a huge barrier. If parents don’t have a way to get to PTO meetings, it’s unfair to assume they don’t care,” she said. “I know those barriers because I once lived them myself as a single mom.”

Her point was underscored by research showing students with engaged families are more likely to earn higher grades, attend school regularly, and see themselves on a path to college or a career. “Engagement must be flexible, culturally responsive, and contagious,” Johnson said.

A Call for Collective Action

By the close of the conversation, the panelists returned to a common theme: no single group can shoulder the burden of improving education in Mississippi. Teachers, families, policymakers, and local leaders all have a role to play.

According to Mississippi’s 2024 accountability grades, districts across the state are showing real signs of progress, with more students earning C or higher ratings than in previous years.

Hudson closed with words from Martin Luther King Jr.:

“Not everyone can be famous, but anyone can be great, because greatness is determined by service. If we close silos and combine our efforts, we can make a difference.”

Johnson called for stability and representation in policy. “Too often, decisions are being made by people who don’t share the experiences of the families they serve,” she said. “Teachers need resources and fair pay. If we care for them properly, imagine how much stronger our schools will be.”

Watch the Full Conversation

Want to hear the full discussion and insights directly from our panelists?

Watch the full Raising the Bar for Mississippi’s Students webinar here.